How do I explain my interests to my mom?

First, let me say that my main interests lie at the intersection of three seemingly distinct branches of mathematics: namely, geometry, topology, and algebra.

What do these fields deal with?

- If we pick two points, can we tell how far apart they are?

- Is there a notion of "going straight"?

- Is there a notion of angle which generalizes the usual one? If so, how can we measure one?

- How do triangles look in different settings?

Topology

Topology and geometry are the branches of mathematics that study the "shape" of objects. The meaning of "shape" is not unique, and this is what differentiates the two fields.

Topology is the coarser cousin of geometry, as the objects we study are not endowed with what in everyday life we would call a "shape", but rather with a more abstract notion of "closeness".

This notion of "closeness" allows us to define what a continuous function is; namely, a function which does not "tear" our object.

Think about playing with a piece of clay: in topology, you can bend it, twist it, stretch it as much as you want, but you cannot tear it apart, punch holes or glue pieces together.

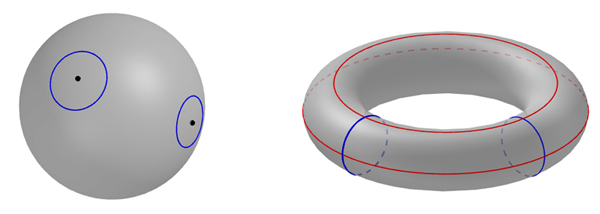

For example, if you have a little ball, you can stretch it into a noodle, you can shape it into a cube, a pyramid, a icosahedron; you cannot, however, glue together the two extremities of the noodle to form a donut shape. You can also turn a donut (or a torus, as I would call it), into a handy mug:

At this point, a question arises naturally: how can we tell that a sphere is not a torus?

This is where the interplay with algebra comes in clutch: while intuitively it should be clear why, as a torus is just a sphere with a hole punched through it (which is not a legitimate move in our book), proving it rigorously is a completely different matter.

Think about actually being either on the surface of a sphere or a torus, together with your dog, and having to determine where you actually are: what would you do?

There is not a unique answer, but one thing you could do is the following: let your dog walk (while holding its infinitely long leash) indefinitely. As soon as the dog comes back to you, pull the leash: if it gets stuck somewhere, you know you are on the surface of the torus.

In a mathematical language, we could say this by saying that the torus admits homotopically non-trivial loops, while the sphere does not. Equivalently, a sphere has trivial fundamental group, while the torus does not.

In a formula, \[\pi_1(S^2)=0, \quad \pi_1(S^1\times S^1)\neq 0.\]

Geometry

Geometry deals with much richer structures, such as metrics and connections. While topology studies a coarse "shape" idea, the much more accurate geometric structures make the following questions (among many others) make sense, which would otherwise not be possible:

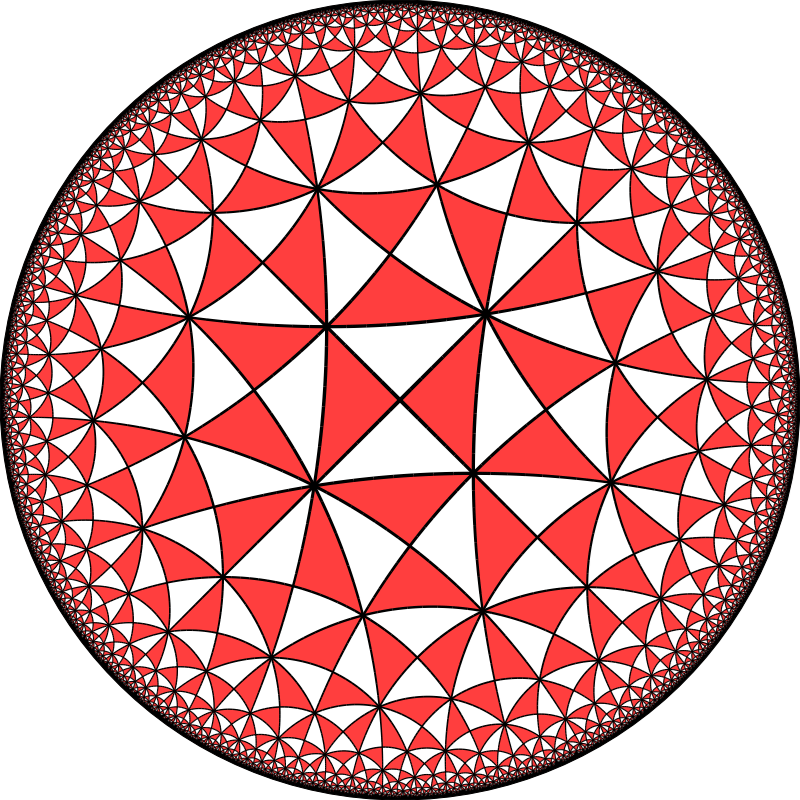

The interplay between geometry and topology is a very deep matter, and some of the most involved questions in one field can be answered using techniques and ideas coming from the other: the most famous example of this is the so-called Poincaré conjecture, a long-standing, purely topological problem, solved using geometrical (and analytical) tools and techniques.

Algebra

Algebra is a branch of mathematics that - in its purest form - studies how patterns arise in seemingly different structures and objects.For example, take a Rubik cube, and enumerate the little squares that make up its faces. The possible moves that you can do on the numbered cube can be composed with each other, they are all reversible, and there is a move that leaves every square fixed (it suffices to simply do nothing). We say that these moves form a group.

The biggest strength of algebra is stripping things of their material meaning (the moves on the Rubik cube become elements of an abstract mathematical object), and studying them from a purely formal point of view. This allows us to see which rules always hold, no matter what we are actually dealing with, as long as we follow the same basic structure.

Why should you care about mathematics?

You do not have to care about pure mathematics, at least directly.

However, probably the most recurring pattern in the history of mathematics is that of a seemingly useless idea, which later on turns out to be useful in a different context, or in a different field. The following are two recent examples:

- The ancient Greeks were studying the distribution of prime numbers 2500 years ago. The RSA cryptosystem, first published in 1977, relies heavily on the fact that prime numbers are sparse enough that factorizing a big number into the product of two primes is almost impossible in due time, and it is widely used nowadays for bulk encryption-decription tasks.

- In 1854 George Boole, a self-taught English mathematician, published a book containing the foundations of modern Boolean calculus for logical statements. While it did not have an immediate application, his work was rediscovered as the first computers came around, roughly 100 years later, and is considered to be the foundation of modern computing.